A Friendly Neighborhood Supermassive Black Hole

Submitted by chandra on Mon, 2019-11-25 16:00

Roberto Gilli

We are very happy to welcome Roberto Gilli as our guest blogger. Dr. Gilli is the first author of a paper that is the subject of our latest Chandra press release. He received his Ph.D. in astronomy from Firenze University in Italy in 2001. Afterward, he did a post-doctoral fellowship at The Johns Hopkins Observatory before returning to Firenze at the Arcetri Astrophysical Observatory. Today, he is an astronomer at the National Institute of Astrophysics (INAF) in Bologna, Italy, a position he has held since 2005. His research interests include active galactic nuclei, quasars, and deep X-ray surveys.

Black holes are usually perceived as dangerous, disruptive systems. On the one hand they swallow copious amount of matter. On the other, they release a large amount of energy in the form of both radiation and matter when enormous quantities of material fall onto them.

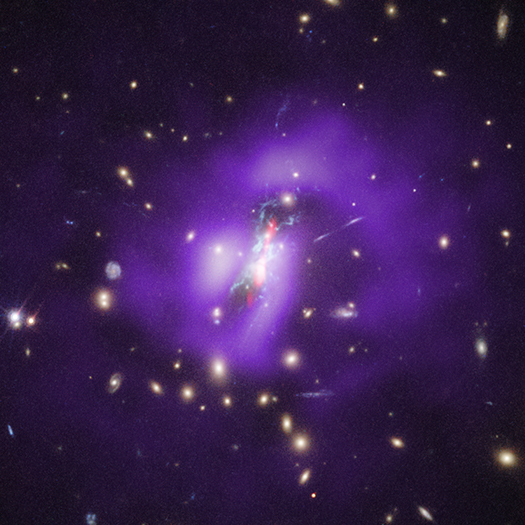

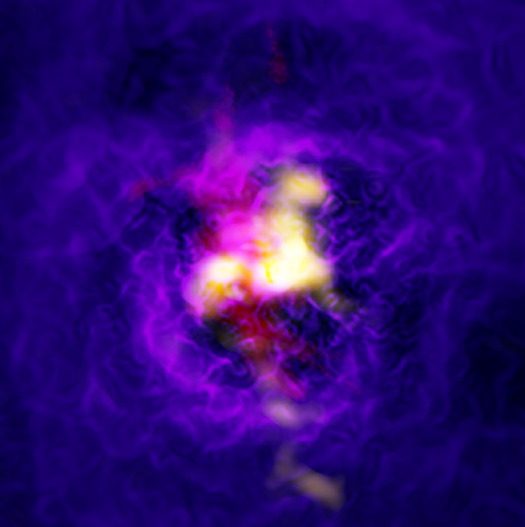

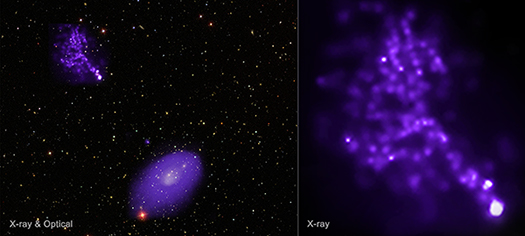

The most extreme manifestation of such phenomenon is known as a "quasar" or an "active galactic nucleus" (AGN) that are powered by growing supermassive black holes (SMBHs) at galaxy centers. During these growth phases, part of the gravitational energy of the infalling gas is converted into strong electromagnetic radiation. Meanwhile, some of the gas, rather than being swallowed by the black hole, is instead accelerated and pushed very far away in the form of fast winds or even faster jets that can approach the speed of light.