A Journey to Becoming a NASA Astronomer

We welcome John ZuHone, an astrophysicist on the Advanced CCD Imaging Survey (ACIS) team at the Chandra X-ray Center, as our guest blogger. Prior to Chandra, he was a postdoctoral researcher at the MIT Kavli Institute, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, and the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian. John received his undergraduate degree in physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and his Ph.D. in astronomy and astrophysics from the University of Chicago. His research interests include merging galaxy clusters and the physics of the intracluster medium.

My interest in astronomy started when I was very young. When I began to read, there was one book that was bought for me that I started taking everywhere—My First Book About Space. The pictures of planets, star clusters, and galaxies taken by telescopes and imaged by the first solar system probes launched by NASA captivated me (I still have this book on my shelf, though it’s a little worn out these days). Another book that I read over and over again was The Stars: A New Way to See Them by H. A. Rey, the writer of the Curious George series. Rey was frustrated by how the constellations were drawn in many star charts—they didn’t look anything like the names they were given. So he re-drew the lines—and most of the time, he was able to make it work! To this day, when I look up at a night sky filled with stars, I see the constellations as Rey drew them.

This knowledge of the stars came in handy. When I begged for a telescope at age six, the only way I knew how to find anything that wasn’t the Moon or a bright planet was to orient myself in the sky using the constellations and then star-hop to the Orion Nebula, the Pleiades, or the Andromeda Galaxy. I grew up on a small farm in central Illinois, so on a clear, moonless night the stars were everywhere. I started logging hours on that little telescope. I learned when the next meteor showers were supposed to happen, and dragged my dad out at 2 am to see them (because I insisted that’s when the person doing the weather on the news said we should go).

The 80s were an ideal time for a small child in America to become fascinated by space. The nation was still basking in the triumph of the Moon landings. NASA had sent spacecraft to Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, and I watched with great anticipation as the Voyager 2 probe made its way to Uranus and Neptune. Like many children, I was sure I was going to be an astronaut. In fact, I told all of my friends that I was going to be the first human to set foot on Mars.

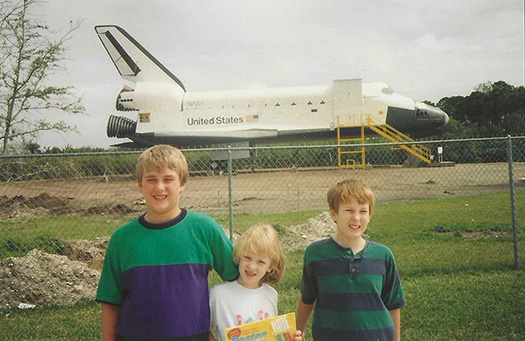

John ZuHone (left) with is sister (middle) and brother (right) in front of Space Shuttle Explorer.

Credit: Shelley ZuHone

I didn’t know it at the time, but my path was going in a slightly different direction. My parents bought a Commodore 64 computer, along with the usual Sesame Street games. I found the manual for the computer in the box, which showed you how to code in the BASIC language. I didn’t always know how to follow the logic, but I could certainly copy the code from the book, and I soon found myself printing my name over and over again, making balls bounce on the screen, and solving simple math equations. I developed a love for computers that rivaled my love for astronomy.

Commodore 64, an 8-bit home computer introduced in January 1982 by Commodore International.

(Public Domain)

These early experiences eventually convinced me by my teens and into college that I wanted to be an astronomer. I am blessed to have been surrounded by my parents, family, teachers, pastors, and friends who provided me with the opportunities and encouragement that I needed to reach this goal, and without which it would not have been possible.

There were certainly setbacks along the way, and times that I wondered if I wasn’t cut out for it. There were rejection letters, homework assignments that I wasn’t able to complete, and research projects that didn’t pan out. All the while, I was pushed and encouraged by my family, professors, and advisors.

Since 2015, I have been an astronomer working for the Chandra X-ray Observatory, NASA’s flagship mission for X-ray astronomy. I work for the team that manages the Advanced CCD Imaging Spectrometer camera on Chandra, which has transformed our view of the high-energy universe. I also perform scientific research in the area of clusters of galaxies, work that is enabled by Chandra’s unique capabilities.

Credit: John ZuHone

I have experienced the thrill of sitting in front of a screen at Chandra’s control center, participating directly in real-time operations, watching as we send commands up to space and the spacecraft actually talks back to us (this amazement doesn’t get old, regardless of how many times you do it). I have developed large computer simulations of collisions between clusters of galaxies on NASA’s fastest supercomputer, and used them to try to unlock the secrets of nature’s most energetic events. Just as when I was a child, I’m using telescopes and computers—the hardware has just gotten a lot better.

Perhaps the best part of the job is explaining it to others, especially children. I have participated in Chandra’s communications and public engagement efforts, and spoken at schools. One fifth-grade classroom I spoke to gifted me drawings that they made of planets, galaxies colliding, and matter spinning into black holes. It was so gratifying to see that what I had shown them had captured their imaginations so much. As a father, I have seen that my own children have gotten the bug—one of my favorite pictures of my son is one of him sitting in front of the computer at Chandra’s control center with a headset on—he’s ready to fly!

The vivid pictures and scientific descriptions that I read in those books and watched on the television so many years ago were only possible because of the amazing work done by astronomers in the US and around the world, and the engineers and astronauts at NASA and other agencies that made it all possible. I look at the work that today’s great observatories and space probes are doing, in which I am humbled to take a part, and I am heartened by the wonderful images that I know are inspiring the children of today, similar to how I was inspired decades ago. I look to the future and know that we can continue to build on this great legacy that has been left to us to continue to push the boundaries of humanity’s knowledge of the cosmos.

Category:

Subcategory:

- Log in to post comments