Studying Comet 46P/Wirtanen During its Close-by Visit Near Earth

Submitted by chandra on Thu, 2019-01-03 09:21

Dennis Bodewits in Japan during the

‘Comets, Meteors, and Asteroids’ conference.

We welcome Dennis Bodewits as a guest blogger. Dennis studies the chemical and physical behavior of comets. He is an associate professor at Auburn University in Auburn, Alabama, and leads a large observing campaign combining multiple NASA spacecraft to study comet 46P/Wirtanen during its close-by visit near Earth. He loves the outdoors, mountain biking in Auburn's Chewacla State Park, and has piloted a human-powered helicopter.

I got into comet research while conducting experiments at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. My work supported fusion — where two lighter nuclei join to create heavier ones — research. To measure the temperature in fusion plasmas, you can't just stick a thermometer in your reactor. Instead, the idea was to let in a little bit of trace gas which would make the ions, that is, atoms that have a positive charge, glow.

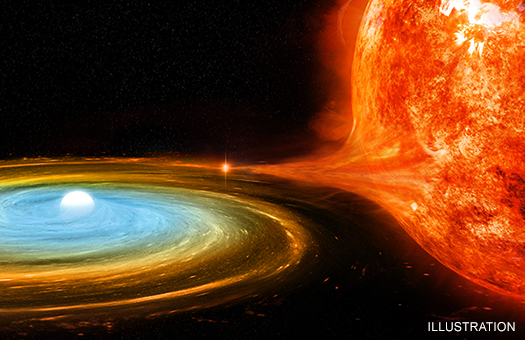

It turned out that the main reaction responsible for this light, charge exchange, had been discovered in comets. Charge exchange is the process where a charged ion collides with a neutral atom or molecule and captures one of its electrons. Light is then emitted as the captured electron moves to a lower energy state. This process is especially important in comets where ions from the solar wind collide with neutral atoms in cometary atmospheres. For my doctorate I worked on trying to find out what I could learn about comets and the solar wind from charge exchange emission, combining lab work with Chandra observations.