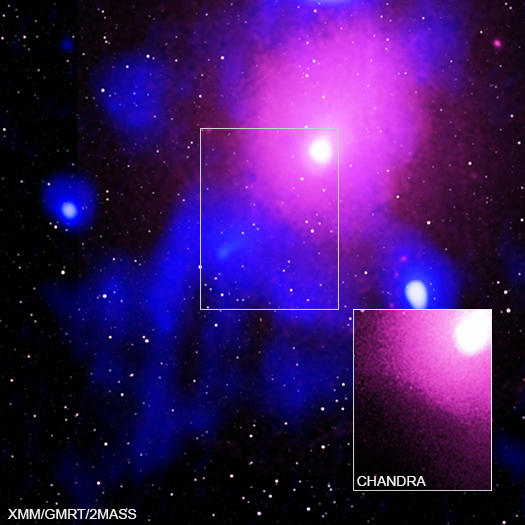

Ophiuchus Galaxy Cluster

Ophiuchus Galaxy Cluster

Credit: X-ray: Chandra: NASA/CXC/NRL/S. Giacintucci, et al., XMM-Newton: ESA/XMM-Newton;

Radio: NCRA/TIFR/GMRT; Infrared: 2MASS/UMass/IPAC-Caltech/NASA/NSFWe are pleased to welcome two guest bloggers, Maxim Markevitch and Simona Giacintucci, who led the study described in our latest press release. Markevitch, an expert on galaxy clusters X-ray studies, got his PhD at the Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. He worked on ASCA X-ray data in Japan, then at the Chandra X-ray Center for the first 10 years of Chandra operations, and is now at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. He received the AAS Rossi Prize. Giacintucci, the lead author of the study, is an expert in radio phenomena in galaxy clusters. She got her PhD at Bologna University. She was a postdoc at the CfA and an Einstein fellow at the University of Maryland, and is now at the Naval Research Lab.

Galaxy clusters are colossal concentrations of dark matter, galaxies, and tenuous, 100-million-degree plasma. This plasma — gas where the electrons have been stripped from their atoms — slowly loses heat by emitting radiation in the form of X-rays. Around the central peaks of many clusters, where matter concentrates, the plasma gets dense enough* to cool quite fast, on a timescale shorter than the cluster's lifetime (a few billion years). The higher the plasma's density, the more X-rays it emits and the faster it cools. As it cools down, it contracts and becomes denser still, and so on, entering a runaway cooling process. Left unchecked, this process should deposit vast quantities of cold gas in the cluster centers.

We know for a fact that the plasma cools down because we do observe those X-rays — but we don't find nearly as much cold gas in the cluster centers as such runaway cooling must deposit. This has been a puzzle for a long while, and the solution the astronomers converged upon is that there must be some source of additional heat in the central regions of clusters — their “cores” — that doesn't let the plasma cool below 10 million degrees or so.

Early Chandra X-ray images of galaxy clusters pointed to the likely source: the supermassive black holes (SMBH) that sit in the centers of the cluster central galaxies, pull in the surrounding matter, and eject a tiny part of it (just before it sinks irretrievably into the black hole) at nearly the speed of light back into the surrounding gas. Where those jets hit the gas, they blow huge bubbles in it, stir it, generate shocks like sonic booms, etc. (all of these features have been seen in the Chandra images of the cluster cores). The current wisdom holds that these processes together supply the needed heat to prevent runaway cooling from occurring, but at the same time are not so powerful that they blow up the whole plasma cloud, implying some kind of a gentle, self-regulated feedback loop may be occurring.