Submitted by chandra on Tue, 2016-05-24 10:08

Fabio Pacucci

Fabio PacucciIt is a pleasure to welcome Fabio Pacucci as a guest blogger. Fabio led the study that is the subject of our latest press release. He is going to defend his Ph.D. Thesis at the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa (Italy), under the supervision of Andrea Ferrara. During his Ph.D. he spent several months at the Institute d’Astrophysique de Paris (IAP) in France, Yale University and Harvard University in the USA. In September he is starting his first postdoctoral position at Yale University. Fabio has mainly been working on understanding the properties of the first black hole seeds, formed when the Universe was less than one billion years old.

It was a sunny and hot afternoon in Pisa when Andrea Ferrara, my Ph.D. supervisor, suggested that I study the first black holes formed in the Universe. This topic is among the most interesting in cosmology. We know that almost every galaxy hosts a supermassive black hole (SMBH) at its center. In the Milky Way there is a black hole about 4 million times more massive than the Sun, but objects up to 10 billion times the mass of the Sun have also been observed.

Submitted by chandra on Wed, 2015-10-21 10:03

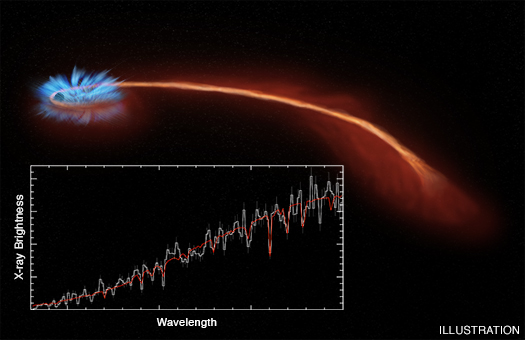

Astronomers have observed material being blown away from a black hole after it tore a star apart, as reported in our press release. This event, known as a "tidal disruption," is depicted in the artist's illustration.

Submitted by chandra on Wed, 2015-09-23 00:17

Gabriele Ponti

Gabriele PontiDr. Gabriele Ponti is the Marie Sklodowska-Curie EU Research Fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Germany. Prior to that, he was a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Southampton in the UK, after spending a year at Cambridge University’s Institute of Astronomy. Dr. Ponti earned his Ph.D. from Bologna University in Italy before moving on to the Laboratories Astro-Particule et Cosmologie in Paris. His doctoral thesis topic was studying relativistic effects in bright active galactic nuclei and he has been interested in this area since then.

As a boy, I read about the existence of black holes for the first time. I still remember the fascination of trying to grasp the physical concepts behind one of the weirdest manifestations of nature.

Black holes produce an enormous gravitational pull, as a consequence of being extremely compact: a significant amount of mass concentrated in a very small volume.

Submitted by chandra on Wed, 2015-09-23 00:06

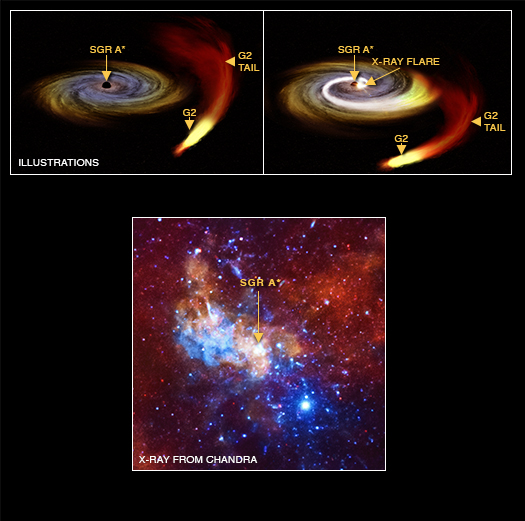

Three orbiting X-ray telescopes have been monitoring the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy for the last decade and a half to observe its behavior. This long monitoring campaign has revealed some new changes in the patterns of this 4-million-solar-mass black hole known as Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*).

Submitted by chandra on Wed, 2015-05-13 12:52

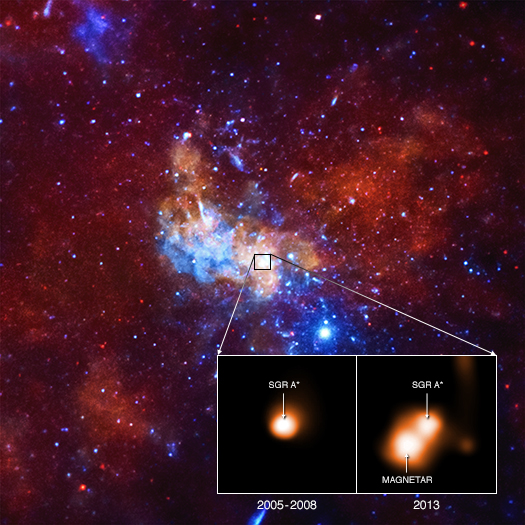

In 2013, astronomers announced they had discovered a magnetar exceptionally close to the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way using a suite of space-borne telescopes including NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory.

Magnetars are dense, collapsed stars (called "neutron stars") that possess enormously powerful magnetic fields. At a distance that could be as small as 0.3 light years (or about 2 trillion miles) from the 4-million-solar mass black hole in the center of our Milky Way galaxy, the magnetar is by far the closest neutron star to a supermassive black hole ever discovered and is likely in its gravitational grip.

Submitted by chandra on Mon, 2015-01-05 13:06

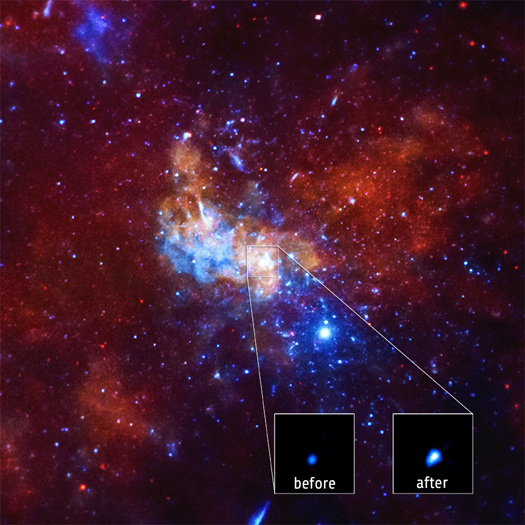

On September 14, 2013, astronomers caught the largest X-ray flare ever detected from the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way, known as Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*). This event, which was captured by NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, was 400 times brighter than the usual X-ray output from Sgr A*, as described in our press release. The main portion of this graphic shows the area around Sgr A* in a Chandra image where low, medium, and high-energy X-rays are red, green, and blue respectively. The inset box contains an X-ray movie of the region close to Sgr A* and shows the giant flare, along with much steadier X-ray emission from a nearby magnetar, to the lower left. A magnetar is a neutron star with a strong magnetic field. A little more than a year later, astronomers saw another flare from Sgr A* that was 200 times brighter than its normal state in October 2014.

Submitted by chandra on Wed, 2014-11-12 00:20

Andrea Peterson

Andrea PetersonWe are pleased to welcome Andrea Peterson as a guest blogger today. Andrea is a co-author of a paper reporting that the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy may be a source of highly energetic neutrinos, as explained in our latest press release. Andrea recently completed her Ph.D. at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she studied particle phenomenology. She is now a postdoctoral researcher at Carleton University in Ottawa, Ontario. She was born and raised in Minnesota, and received her undergraduate degree from Harvard University. She hopes to live somewhere warm someday.

Neutrinos are tiny particles that zoom through the universe at nearly the speed of light. They interact very rarely, so most of the time they pass right through you, me, or any object they encounter. Their ghost-like nature can be a boon for astronomers: they travel from their sources without getting absorbed or deflected. We can use neutrinos to get a clear picture of the very distant universe.

You may have noticed a problem, though. If they don’t interact very often, how can we catch them here on Earth? They have to interact with our detector to be seen!

The solution is size. The bigger the detector, the more stuff there is for the neutrinos to bump into, increasing the chances of detection. The IceCube Neutrino Observatory, located at the South Pole, uses a cubic kilometer of ice to trap neutrinos. In three years, this giant detector has collected 36 extremely energetic neutrinos that are likely to have come from astrophysical sources.

Submitted by chandra on Wed, 2014-11-12 00:10

The supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way, seen in this image from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, may be producing mysterious particles called neutrinos, as described in our latest press release. Neutrinos are tiny particles that have virtually no mass and carry no electric charge. Unlike light or charged particles, neutrinos can emerge from deep within their sources and travel across the Universe without being absorbed by intervening matter or, in the case of charged particles, deflected by magnetic fields.

Submitted by chandra on Wed, 2014-10-08 12:32

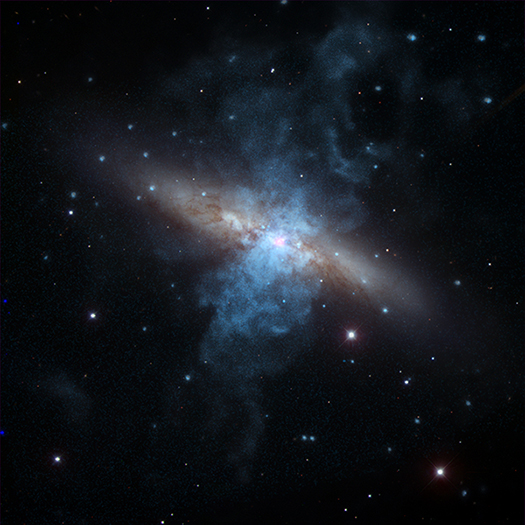

An Ultraluminous X-ray Source (ULX) that astronomers had thought was a black hole is really the brightest pulsar ever recorded. ULXs are objects that produce more X-rays than most "normal" X-ray binary systems, in which a star is orbiting a neutron star or a stellar-mass black hole. Black holes in these X-ray binary systems generally weigh about five to thirty times the mass of the sun.

Submitted by chandra on Wed, 2014-03-05 11:44

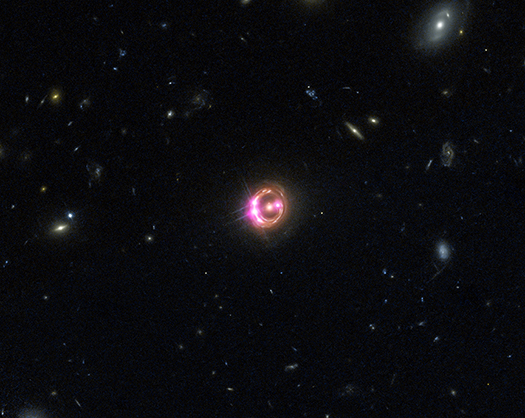

Multiple images of a distant quasar are visible in this combined view from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and the Hubble Space Telescope. The Chandra data, along with data from ESA's XMM-Newton, were used to directly measure the spin of the supermassive black hole powering this quasar. This is the most distant black hole where such a measurement has been made, as reported in our press release.

Pages