Disclaimer: This material is being kept online for historical purposes. Though accurate at the time of publication, it is no longer being updated. The page may contain broken links or outdated information, and parts may not function in current web browsers. Visit chandra.si.edu for current information.

The Race to Explain a Star's Mysterious Cooling

by Peter EdmondsFebruary 23, 2011 ::

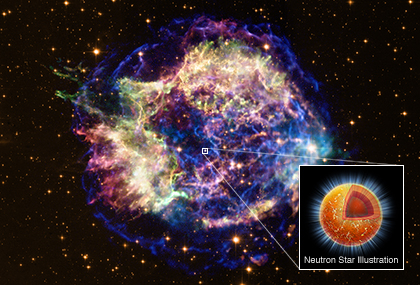

Two new reports have uncovered remarkable details about the interior of a tiny star located in our Galaxy about 11,000 light years from Earth. These results, announced in this press release, reveal a superfluid forming in the neutron star in the famous Cassiopeia A (Cas A) supernova remnant. This unprecedented result supports the idea that neutron stars contain the vast majority of all superconducting and superfluid matter in the Universe.

The story behind this announcement is also interesting, and involves some healthy competition and a tight race to explain the mysterious cooling of this neutron star. There are striking similarities between the two different papers, one led by Dany Page from the National Autonomous University in Mexico, and the other by Peter Shternin from the Ioffe Institute in St Petersburg, Russia. The studies were conducted by independent research teams, yet they obtained almost identical results and were submitted for publication only one day apart.

The detection of a faint X-ray point source at the center of Cas A in 1999 was one of the first scientific results from Chandra, but it wasn't until 2009 before a good theoretical model for X-ray emission from this neutron star was published in Nature [1] by Wynn Ho from Southampton University in the UK, and Craig Heinke, from the University of Alberta in Canada. They realized that their estimate of the neutron star's surface temperature would be important for understanding how such objects cool and evolve, and began collaborating with a team led by Dmitry Yakovlev and Shternin, from the Ioffe Institute in St Petersburg, Russia. However, they had just a single temperature measurement and did not realize that much more information was waiting to be discovered about the star's temperature.

In March 2010, a collaborator asked Ho whether the Cas A neutron star was cooling. Heinke looked into this, and using multiple Chandra observations of Cas A, he found a clear and unexpectedly large temperature decline of about 4% over ten years, once some calibration problems were solved. The result was quickly written up, submitted to The Astrophysical Journal Letters [2] and accepted, and Heinke placed the paper on astro-ph on Tuesday, July 27th, 2010. Only a few days later he received this excited email from Page:

Dear Craig and Wynn,

I just found your paper on cooling of Cas A:

Just AMAZING !

Cheers,

Dany

In Heinke's words, "that's the kind of email one loves to get!" Page's email to Heinke did not exaggerate his excitement, because there are 31 emails in his "Cas A" file during the weekend of July 31st, and he wrote to his collaborators - Madappa Prakash (Ohio University), James Lattimer (State Universty of New York at Stony Brook), and Andrew Steiner (Michigan State University) - recommending that they interpret this cooling and get a paper out by the next Monday, before Yakovlev and his colleagues did!

Page was right about his competitor's plans, but the star's cooling seemed too rapid to be easily explained by either team. But then, in the middle of September, Shternin enjoyed a "eureka" moment after hiking in a rugged part of Russia and encountering some very steep slopes. He woke early the next morning and went back to the Cas A cooling data. He knew that the onset of superfluidity would help explain the rapid cooling, but realized that this wasn't enough to explain the large drop in temperature. But, then he remembered his mountain climbing and thought, "if you want to have a steeper slope, just raise the top level." Adding in a proton superconductor that formed much earlier in the lifetime of the star played this role, because it slowed down the early cooling of their model neutron star. This kept the temperature high before the cooling from the neutron superfluid kicked in a few hundred years later, giving a steeper slope for the temperature decline.

Shternin started writing a paper with Yakovlev, Heinke, Ho and Dan Patnaude (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) about these new results. However, they were waiting for a new Chandra observation of Cas A to check that the cooling was continuing as expected. The data were available by November 5th, but Heinke had a busy teaching and research schedule and didn't get to the data right away.

This would work in Page's favor. After his initial excitement at seeing Heinke and Ho's paper at the end of July, Page also had difficulty explaining the rapid cooling of the star, so he postponed working on it "to tomorrow and the tomorrow became, as usual self generating!" But then a conference approached where he was scheduled to give his usual talk about neutron star cooling, a prospect that he did not find very stimulating. So, he decided to turn "the tomorrow into a today and just do it, to have something new and exciting to talk about."

Madappa Prakash recalled how frustrated Page was, in the numerous emails they exchanged, before a light bulb went off in Page's head about the effect of proton superconductivity to accelerate the cooling. Page's jubilant e-mail said, "I got it," and left his colleagues waiting to figure out what it was that he got. He explained the details in his conference talk on November 18th and was approached afterwards by Sharon Morsink, a colleague of Heinke from the University of Alberta. Morsink told Page, "Craig will be glad to know you're working on his data." Page knew that the clock had started ticking, since Morsink would report back to Heinke about Page's progress. It was now very clear that the race between the two teams was on and Page worked even harder than before to write his paper.

Heinke's reaction to Morsink's news was, "oh no, I've delayed the paper and now we'll get scooped!" Heinke immediately analyzed the last observation that weekend and on November 27th he emailed his collaborators both his results and a report about Page's talk. Yakovlev was sure Page would submit soon, but thought they should finish their paper quickly and "hope to compete." But, it was too late. On November 29th, Page emailed Ho and Heinke the paper that he had just submitted to Physical Review Letters [3] and was posting to astro-ph that day. Heinke emailed back, congratulated him and explained they were working on a similar paper.

Shternin and his co-authors considered submitting and posting to astro-ph the same day, but decided not to because such a paper wouldn't include the new observation. They waited another day for Heinke to "frantically scribble down a couple of paragraphs on the observations, some of which I did standing outside, holding my laptop during an ill-timed fire alarm." They finished the paper and submitted to the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS) [4] and astro-ph the next day, November 30th.

So, Page's team won the race, but with Shternin and co-authors so close behind that the submissions were effectively simultaneous. The papers both received good reports from referees and were soon accepted.

This story explains the similarity in timing between the two papers, but not the similarity in the results. The obvious explanation is that they have both explained, independently, what is really happening in the core of the Cas A neutron star. This is an important advance in understanding these remarkable stars and especially noteworthy because no other neutron star is likely to provide a similar opportunity in the near future.

Competition plays an important role in motivating scientists. The prospect of "going where no-one has gone before," at least in an intellectual sense, is a key part of the allure of research. Also, astronomers, like other scientists, are smart, ambitious people who are used to doing well academically. So, competition has been a natural part of astronomical research for a long time. Recent examples include the discovery of observational evidence for dark energy and the estimation of the Hubble constant. There is also intense competition for observing time on telescopes like Chandra and Hubble, which are heavily oversubscribed. All of this competition has sometimes intensified into rivalry or even animosity between different groups, presumably because the stakes have been perceived to be very high, or because minor problems and personality clashes have escalated.

These problems do not appear to have been an issue at all for the Page and Shternin teams, who clearly respect and admire each other, and behave accordingly. For example, both teams have generously argued that the other team should be mentioned first in early press articles that appeared. So, while competition motivated them to work more quickly, their working relationship remained very cordial and professional. They deserve a significant amount of credit for their scientific work and for their responsible behavior.

References:

- Ho, W. & Heinke, C., 2009, Nature, 462, 71 (http://lanl.arxiv.org/abs/0911.0672)

- Heinke, C. & Ho, W., 2010, ApJ, 719, L167 (http://lanl.arxiv.org/abs/1007.4719)

- Page, D., et al, 2011, PRL (http://lanl.arxiv.org/abs/1011.6142)

- Shternin, P. et al., 2011, MNRAS (http://lanl.arxiv.org/abs/1012.0045)

Disclaimer: This material is being kept online for historical purposes. Though accurate at the time of publication, it is no longer being updated. The page may contain broken links or outdated information, and parts may not function in current web browsers. Visit chandra.si.edu for current information.