Here Comes the Sun

Ok, I know this is not an original title for a blog about the sun and certainly not for the new solar cycle. Hey, I am an astronomer, not a writer. Like most science, my work on the Sun is partially something I fell into. My job on the Chandra science team is Monitoring and Trends Scientist. This means that it is my job to watch the spacecraft and make sure nothing is going to go wrong. To be honest, there are a whole bunch of engineers who have the same job for a specific part of the spacecraft and a chief engineer who monitors the whole spacecraft. This leaves me as the utility infielder. That is, when something that we didn't plan for back in 1995 becomes a concern, it usually falls to me.

And so it was with the Sun. The expectation was that the Sun would only affect Chandra during very large solar flares -- the type that cause the northern lights to be visible in Boston, cause static on your cell phone and occasionally cause power blackouts. These happen about once a decade or so, and, while annoying, their rarity makes them something we can plan to live with a deal with when they happen, like the occasional blizzard in April.

Instead, we found out that moderately elevated level of protons coming from the Sun could damage our detectors especially the ACIS. Such events are relatively common and during the first seven years of the Chandra mission there were over 60 events that caused us to “safe” the spacecraft instruments and ride out the storm. However, we have had no such events since 2006 when the last "solar cycle" tailed off.

The solar cycle is a phenomenon on the Sun that has been observed since Galileo first (recklessly) turned a telescope to the Sun (NEVER DO THIS UNLESS YOU HAVE APPROPRIATE EQUIPMENT -- GALILEO WENT BLIND).

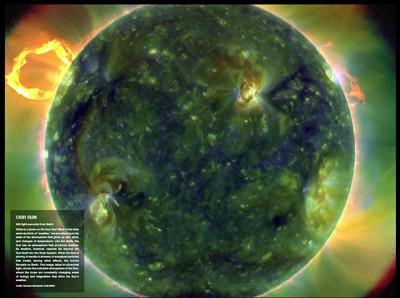

Essentially, over of the course of about 11 years, the number of sunspots goes from near zero to about 100-200 per month. The spots also change in latitude, starting at about 30 degrees and progressing towards the equator over the course of the 11 years. The spots are associated with strong magnetic fields and flares. These are phenomena observed by solar X-ray observatories including TRACE, Hinode, and the recently launched Solar Dynamics Observatory. I use Chandra to observe similar phenomena on other stars.

Ultraviolet image of the Sun from the Solar Dynamics Observatory

The new solar cycle started in early 2009. Because of this, we soon expect the break from radiation shutdowns, which we have enjoyed for the past three and half years, will come to an end. In the coming posts, I'll try to describe our work related to the new solar cycle.

The hope is to provide an insight to the kind of day-to-day work we all do here (and on other missions like Hubble, Spitzer, Swift, etc.) to ensure their long-term health. It turns out that the new solar cycle has been much calmer than the previous one, but I'll discuss that more next time.

-Dr. Scott J. Wolk

July 9, 2010

Category:

Subcategory:

- Log in to post comments